by Gini Graham-Scott | Apr 10, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Books

When you are searching for a publisher for your book, don’t only target publishers who are interested in your type of book but the editors who handle that subject. The way to do this is by using keywords, such as “historical,” “relationships,” & “self-help”.

Although this is not a perfect science, since these searches will pull up some editors who still don’t handle that particular type of book within the category selected. But at least, this kind of targeted search will help to narrow the field.

When you do this search, there are a number of sources you can use, such as the Writers Market directories that come out annually, the Literary Marketplace, which has an online database of publishers, the Publishers Marketplace, or some companies that sell data. However, using such sources of information can be expensive and time consuming – and some data can be out of date.

For example, the Writers Market directories for publishers, agents, and children’s publishers and agents which come out in September for the following year are about $25 each. But because of the delay in publishing and distribution, some of the contact information may have already changed or some companies may be out of business. There is an online directory you can access after buying a book, but you have to do individual searches, and some of the information may not have been updated.

In the case of Literary Marketplace, you need a paid subscription to get more than a physical address, and the cost is $25 for a week, $399 for a year; Publishers Marketplace has a subscription fee of $25 a year. The other companies that sell data have other fees, and typically they only sell you a portion of their total database or allow you to send queries to a limited number of publishers who you have selected from their database.

But even if you have a direct access to the data, you then have to select the publishers to contact individually and create a mailing list or database from that. Then you have to do individual mailings unless you create your own database for multiple mailings.

By contrast, a company like Publishers Agents and Films has already bought the books and subscriptions has created a database with keyword codes to indicate what a publisher is interested in, do their own test mailings every 4 to 6 weeks to update their databases with the latest information, and can do targeted mailings for you within a day of getting your final letter. Plus, the company uses special software to personalize an email to the selected contacts and can use anyone’s email for the “send” and “reply” addresses, so interested editors and publishers think you have written personally to them and reply directly to you.

The big advantage is that you don’t have the time and expense of creating the contact list and you can quickly send out your personalized query letter to several hundred editors within minutes – not the usual days it might take you if you send out individual queries.

Also, consider the letter you send out. It has to be written well and have a compelling and specific subject line to get recipients to open the letter. Often writers who might be great in writing their books don’t know how to write a good query letter. Some common errors are writing a letter which is too detailed or too vague, uses sales or PR hype so it sounds too promotional, or doesn’t quickly convey what the book is about and offer to send more information (such as a synopsis, proposal with sample chapters, or the complete manuscript). Then, too, some writers put in information that is a deal breaker, such as describing a self-published book, which most publishers won’t consider, unless it has had strong sales of thousands of books. So it can sometimes by more effective to work with a company with experienced writers who can review your letter and make any suggestions for rewriting if necessary or can write your letter for you.

Finally, think about the stats for sending out your letters. How many letters are actually delivered? How many are opened? One company that monitors such stats is Publishers Agents and Films which has sent out about 1500 queries for clients. It has found that about 90-95% of the queries are delivered for book publishers and agents, and they open about 60-75% of these queries, with no unsubscribes or spam reports and a very small .20% bounce rate, because of the regular updates.

For more information on selecting publishers, along with writing an effective query letter, you can contact Publishers Agents and Films at www.publishersagentsandfilms.com. You can email publishersagents2@yahoo.com or call (925) 385-0608.

* * * * * * *

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on the film industry: THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO WRITING, PRODUCING, AND DIRECTING A LOW-BUDGET SHORT FILM and FINDING FUNDS FOR YOUR FILM OR TV PROJECT, both published by Hal Leonard.

She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 scripts for features, has three other films in preproduction, and has one feature film she wrote and executive produced in post-production for release in November 2014.

She also writes scripts for clients, and has several film industry Meetup groups which have meetings to discuss members’ films. She is a writer and consultant for The Publishing Connection.

by Gini Graham-Scott | Mar 19, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Books

Since the development of the e-book and its growing popularity, the problem of piracy has become pervasive. The reason is that it is easy to copy and pass on ebooks, and a growing number of piracy sites have made these available. And many other sites which sell ebooks for authors and publishers have pirated books uploaded by others and they remain there, until the site owner is made aware that the material is pirated and is asked to take it down.

Even using digital rights management (DRM) does little good, although it is designed to prevent a user from transferring a file from one platform to another or sharing that file with others.

However, pirates can easily break that code. Also, it is now relatively inexpensive to scan a print copy of a book to make a digital file. I had a series of books scanned for only $2.50 a book, since the cut up pages can be put through an automatic feeder; there is no longer any need to scan them by hand.

Another difficulty in stopping piracy is that the dedicated pirate sites are often located in other countries, and the owners of these sites can easily put up new sites under another name. Moreover, once a book is pirated by one site, it can easily be spread to multiple sites – making the problem of getting one’s books off of pirated sites like a game of whack-a-mole – hit the mole down at one site, and it quickly pops up in another.

So what can you do to protect yourself from piracy? While you probably can’t overcome the problem entirely, here are some things you can do.

1) Register your copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office, which is easy to register online for only $35 for a single application; $55 for two or more authors. This registration will give you the authorization to send out takedown notices, though trying to enforce a copyright through legal action is unlikely.

2) Inform your publisher to send out a takedown notice or send out this notice yourself to the website owner. If the owner does not respond in a reasonable time, say 10 days, send the takedown notice to the service hosting the website. Normally, the hosting service will take down any infringing material within a few days, since if it doesn’t the service can risk being shut down or being blocked by search engines. You can also send a notice to Google about the violation of your copyright, since Google will lower the search rankings of websites that sustain a number of complaints, and if they get enough complaints, they will block those sites entirely. There are specific requirements for what to include in these notices which you can find online or in my book THE BATTLE AGAINST INTERNET BOOK PIRACY.

3) Find ways to adapt to this piracy to promote your writing or sell other materials, such as by including information in your books that direct those reading them to your website where you have other protected materials for sale or you are selling your writing services to others. Some writers also use piracy as a way to spread their name generally so they have a higher profile in selling other books to publishers.

While it is probably futile to pursue any litigation against the pirates yourself, since any action is extremely expensive and time-consuming, and only the bigger publishers acting individually or with other publishers can afford to do this, as did John Wiley in suing a pirate site in Germany for one of its Dummies books, at least there is some consolation in the risks of obtaining pirated books. In some cases, individuals obtaining these books end up with malware that opens up their computer to identity theft or corrupts some of their data. And sometimes pirates are targeted by a larger publisher or by law enforcement when their actions are especially egregious or they are involved in uploading or downloading material to one of these targeted pirate sites.

In sum, make sure your book is copyrighted by your or your publisher, send out takedown notices as you can, do your best to use the piracy to promote or sell your other work, and feel some satisfaction in knowing that many pirates will suffer their just deserts in the end.

* * * * * * *

GINI GRAHAM SCOTT, Ph.D., is a nationally known writer, consultant, speaker, and seminar/workshop leader, who has published over 50 books on diverse subjects, including business and work relationships, professional and personal development, and social trends. She also writes books, proposals, scripts, articles, blogs, website copy, press releases, and marketing materials for clients as the founder and director of Changemakers Publishing and Writing and as a writer and consultant for The Publishing Connection (www.thepublishingconnection.com).

She has been a featured expert guest on hundreds of TV and radio programs, including Good Morning America, Oprah, and CNN, talking about the topics in her books.

by Gini Graham-Scott | Feb 19, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Books, Marketing Tips - Films

Co-writing and ghost writing arrangements for both books and scripts can be great when you and your co-writer or lead writer have a shared vision for the project and you bring to it complementary skills. Besides writing my own books and scripts, I have worked with several dozen clients on co-written projects.

A first step is understanding what the person seeking a co-writer or ghost writer wants and clarifying what you will do. In reaching this understanding, determine this person’s goals – is this to be a proposal for a books and some sample chapters, a complete book, a treatment for a film, a complete script, or whatever else the person wants written.

Also, work out the financial arrangements, including whether the client will be paying for this as a work for hire or as a co-writing arrangement, or if this is starting out as a work for hire, which will be transformed into a co-writing project if you mutually agree. Then, too, determine how the client will pay – based on a per word or per page basis or an hourly rate – and if it is per page, clarify approximately how many words per page this will be, based on the type font you are using.

Additionally, determine up front how the client will pay. Some like a contract, where you get a certain percentage down (ie: 20-33%), another percentage after you complete a certain amount of the manuscript (ie: another 20-33% after you complete ¼ to ½ of the manuscript), still more at the next percentage point, and at the end. Another common alternative is to use a pay as you go model, where the person pays you a set amount via PayPal or check for each segment of the project before you do it or where you charge that person’s card a certain amount before or after you do each section.

With more established companies, a common arrangement, if you don’t have a contract for money up front for each section of the project, is for you to bill the company, after which they pay you within 10 to 30 days. And usually they do. While such a billing arrangement may be fine with larger established companies or with a client with whom you have an ongoing long-term relationship, I don’t recommend this for new individual clients, especially if you haven’t met them personally or they are in another state or country. The big problem is that you can do the work and they don’t pay you. Then, you have little or no way to collect, because the client is out of state and this is too small amount to pursue through legal means, plus then you still have to collect if you win.

Sometimes clients may argue that they don’t want to pay anything up front because they aren’t sure that you will complete the work or that they will be satisfied. One good response to that is to assure them that they are protected if they pay you by credit card, because they can ask for and obtain a refund from their credit card company for non-completion of the project, whereas you have no such protection if they don’t pay you. As for their comment that their payment hinges on whether they will be satisfied, this could be a red flag that you are dealing with a difficult person who is hard to satisfy, and they could refuse to pay you for that reason, too.

To deal with that issue, I generally respond that I don’t work on spec and that I can limit what I do to a small number of pages (say 5-10 pages). Then, they can provide me with their comments so I can revise what I have written if necessary, and if satisfied, they can give me the go ahead to do more. But otherwise, I get paid for what I do, and I will do everything I can to make sure they like what I am doing, before I do more.

Another arrangement I will enter into with some clients is an initial co-writing agreement if the project is in my field and I think I will like working with this person, if the person insists on such an arrangement to do the project. Then, I will deduct 25% from my usual charges in return for a credit and splitting any royalties or fees for selling the project, after deducting whatever the person paid me upfront, though I give the client the option of turning the project into a work-for-hire before pitching it for sale by paying me the additional 25%. But ideally, I prefer to start as a work-for-hire arrangement with the option of turning this into a co-write down the road. This way, it is very clear that client is in control from the get-go, and as the project goes along, we can mutually determine if a co-writer arrangement would be mutually beneficial. Otherwise, the client is in the driver’s seat, steering the project, so he or she knows the destination, and my role is to help the client get there. The advantage of this arrangement, I have found, is that there are no problems of co-writers discovering they have different shared visions of the project as they go along, since it starts with the client’s vision and can always turn into a co-write if this vision is shared.

* * * * * * *

GINI GRAHAM SCOTT, Ph.D., is a nationally known writer, consultant, speaker, and seminar/workshop leader, who has published over 50 books on diverse subjects, including business and work relationships, professional and personal development, and social trends. She also writes books, proposals, scripts, articles, blogs, website copy, press releases, and marketing materials for clients as the founder and director of Changemakers Publishing and Writing and as a writer and consultant for The Publishing Connection (www.thepublishingconnection.com). She has been a featured expert guest on hundreds of TV and radio programs, including Good Morning America, Oprah, and CNN, talking about the topics in her books.

by Gini Graham-Scott | Jan 13, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

In order to properly position and promote your film, you need very good, professional-looking art work for your poster and screener cover, and later this poster art can be used for your home video cover, sales on your website, catalog sheets, and other materials.

Having good art will help your film stand out, convey what it is about, and show you have a good film, since you have taken the care to make it good. Also, whether you pay to have a professional design your art or have some who’s very good with graphics on your team, good art conveys the high value placed on the film, which is important when a distributor seeks to sell it. By contrast, if you have amateurishly looking art, that will detract from your film, no matter how well-done, by making your film look like an amateur effort, since the value of the art transfers to the perception of the quality of your film. Consider this art like a book or music album cover which helps sell the book or album.

If you don’t have a top-notch graphics designer on your team and can afford it, hire a top professional. Figure the cost will be about $1000-3000. You might find some good contacts in your area through a local Chamber of Commerce directory or a business mixer. Other possibilities include business referral and networking groups, such as BNI (Business Networking International), which has chapters all over the U.S. in major cities. If you have a limited budget, to keep your costs down you might find someone through a local college or art school. Just contact the school’s placement center or ask an instructor teaching a class on graphics design to tell the class about your job opportunity. You might also have some success posting a notice for a designer on Craigslist or going to one of the freelance websites that feature work by freelancers who work at a lower rate, largely because they are located outside the U.S., such as www.guru.com or www.elance.com. Years ago I hired someone through Elance from Australia, and I hired some students from San Francisco State for some art projects.

To choose someone with the kind of style you like, look at the prospective designer’s portfolio – either through a personal meeting or online. To help determine the look and feel of your film, look at some covers and posters for other successful films in your genre to see the approach used. For instance, if it’s a horror film, you will probably want dark, somber tones that convey mystery and danger. You may want to incorporate images of ghosts, injuries, weapons, or other sorts of destruction and fear are conveyed in your film. As an example, if your film takes place in a haunted house and nearby cemetery, where many characters are attacked or die, incorporate images of the house and gravestones, along with people falling down and perhaps bleeding onto the cellar steps or graves. Alternatively, if your film is a romantic comedy, use light colorful graphics to convey that this is a happy, humorous film, and perhaps feature the romantic couple having fun together. For more specific guidelines, go to a store that rents or sells videos or look online where these videos are on sale to see the posters or covers. While the big video stores are gone, many videos are available at your local supermarket, drug stores, or other venues.

Once you have chosen your graphics artist or have narrowed down your search to a few artists, start with some sketches to illustrate the concept or concepts you are considering for the final art. It can also be helpful to get some feedback or suggestions from others on how they see the film’s poster and cover. In some cases, you might use a preliminary poster that you previously used in pitching the film to interest cast and crew to participate, and that can be a starting point for your final poster and cover.

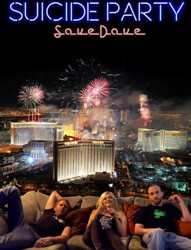

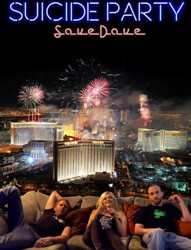

For instance, in the case of SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE, the director was also a skilled graphics designer, who had previously created posters and screen covers for over a half-dozen previously distributed films. So he already knew how to create a powerful image to present the film. Initially, he created a light-hearted but quickly drawn poster to show the film was a comedy drama, though a little dark in light of the words “suicide party” in the title. But this initial design was not intended to be the final poster or cover art.

Later, after the trailer for the film was completed and he was working on the final art, he wanted to have a strong image conveying the excitement of Las Vegas in the video, since the city played a central role in the film. Also, he wanted to include a photo of the three main characters enjoying themselves there, as the primary lead Dave sought to raise money for the party, while his best friend Steve, filmed the action for a crowdfunding campaign being run by his wacky friend Gidget. But he was open to other suggestions.

Though I proposed creating a composite image of the three main characters in the desert looking at Las Vegas as a symbol of hope in contrast to the desolation of the desert, where Dave is contemplating his future and plans for the fundraising campaign, ultimately that concept wouldn’t work, since during filming, there were no shots of the three lead characters together. So ultimately the image became a mash-up of the three lounging on a couch, with the fireworks lighting up the night skies of Vegas behind them.

Besides the title for the film, include the names of the lead actors on the poster art, and you might additionally include a short catchy line, sometimes called a “tag line” or “slogan”, which sums up what the film is about, if it adds to the image. Alternatively, whether you use this tag line on the poster or not, you can readily use it on the back cover of the screener box or in your promotional copy, such as my suggested line for SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE: “If all seems lost, would a suicide party help?”

Before you finalize the art and any slogan or tag line, it’s a good idea to test it out not only with some cast and crew members, but with others who are following the progress of the film. For instance, the SUICIDE PARTY director posted two possibilities of a final cover — one with the fireworks over Vegas, the other with Vegas coming alive at night — on Facebook and asked people to share their comments and preferences. The result? The fireworks over Vegas image was the clear winner, so that’s the image he decided to use, though as of this writing, the tag line and whether to use it on the cover is still being tested.

Once you have this final art selected, use it for the poster, screener box cover, postcards, press kit cover, website, and anything else with graphics for the film, since this image will become like a brand for your film. Having great art helps to not only show it’s a great film, but you reinforce the film’s image in the mind of potential distributors, buyers, the press, and the public, and show it’s an exciting, professionally done film, thereby furthering the odds that people will want to promote, sell, and see it.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on films: HOW TO WRITE, PRODUCE, AND DIRECT A LOW-BUDGET SHORT FILM and FINDING FUNDS FOR YOUR FILM OR TV PROJECT. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 feature scripts, and has one feature she wrote and executive produced to be released in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gus | Jan 11, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

There are two approaches for assessing distributors. One is do an assessment before you contact distributors to decide who to contact in the first place. The other is do this review after you have contacted many distributors, such as through a personalized email query blast where you describe your project and ideally include a link to a trailer, after which some distributors express interest in learning more.

Unless you have personal referrals or have met distributors at an event, such as a conference or workshop, I prefer the email query approach as more efficient, since you use the initial query to target distributors who might be interested. Then, if you get a high level of interest, you can assess the distributors to decide those to follow through with by sending them a screener and promotional materials. You can readily add additional distributors to his initial list. Or simply send all the distributors who have expressed interest the screener and promotional material, and do your assessment afterwards of the remaining interested distributors .

Whatever your initial approach, doing the assessment in advance to decide who to contact or doing it afterwards to decide which still-interested distributors to consider making a deal with, here are some factors to consider in making your assessment and selecting a distributor for all or selected channels and territories.

One approach, especially if you think your film is good enough to go theatrical and you are willing to make the necessary investment for marketing, is to look at the success of these distributors with previous films, as well as whether they distribute your type of film. For example, some distributors specialize in action/adventure films, others in sci-fi, documentaries, comedies, or drama, and some cover most types of films. You want to target those that best fit your film in making initial queries or discussing your film’s prospects after distributors have expressed interest.

One good source for assessing distributors is looking at their profile on IMDB (the International Movie Database) to see how many films they have distributed, when they did so, what type of films these were, and how well these films did. After you review their profile and get a list of their films, you can check the listing for each film to see its description, the cast, and the film’s current rating. You need a professional IMDB subscription to do this, which is around $20 a month, so sign up if you don’t already get this.

That’s the kind of assessment I did in arranging distribution for SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE. After I sent out an email query and about 20 distributors expressed interest and wanted to see the screener, I forwarded their letters to my director, who had previously filmed and distributed over a dozen films, so he could review and rate the distributors. He then came back with his report, indicating which distributors had the best track record after eliminating those who had only distributed a few films, and in one case, only a single film several years earlier. You can’t always get this kind of information from the directories of distributors, so you need to do this checking.

If you have a choice of multiple distributors, this approach can help you find the distributor who is likely to do the most for your film, due to his or her past performance. However, you still need to evaluate the contract and deal you are being offered to determine if that is still the best distributor for your film.

For example, if a good distributor wants a 50-50 deal, while a distributor with only a limited track record wants 35%, it may be better to give up a greater percentage, since, as my director put it, “Thirty-five percent of nothing is nothing.” On the other hand, many distributor deals are for 35%, especially if a distributor feels you have a strong film, and some new distributors may turn out to be very eager and hungry, so they will be very proactive in pushing your film.

Another consideration is whether a distributor expects any money from you for P&A (promotion and advertising) or E&O (errors and omissions) insurance.

Another approach if you want to go theatrical is to look at which distributors are most active in distributing films playing at theaters, along with the genres, grosses, and the number of theaters in which these films have played. This way you can rank the distributors for your type of film based on their box office performance, taking into consideration both the number of films these distributors have represented and the films with the highest grosses.

While you can get the weekend box office grosses for nearly 100 films a week for many previous months, I would suggest just using the Weekend Domestic Chart for the past month to make your analysis more manageable. While the big budget grosses as might be expected are from big studio distributors and their affiliates, some independent distributors have respectable showings of $50,000 or more at the box office, and some have films which have gotten $15,000 or more. Take into consideration the total grosses and how many days the film has been out, so you can more realistically assess how well a film has done during its box office run.

For example, when I did this for the four week period from November 21-December 12, 2014, I found the following distributors for the most films in all genres, although when you do this, limit it your genres. All of these genres include the following:

– Drama

– Thriller/suspense

– Comedy

– Adventure

– Black Comedy

– Horror

– Western

– Action

– Documentary

– Romantic comedy

– Multiple Genres

Based on these listings for this period, these distributors had the highest grossing films, and most of these distributors had multiple films in different genres. I have listed the distributors based on their total grosses for at least one film. In doing your analysis, keep track of the number of films from a distributor, the genre, and the individual grosses.

Gross of $2 Million or More

– Lionsgate

– 20th Century Fox

– Paramount Pictures

– Walt Disney

– Universal

– Focus Features

– Fox Searchlight

– Weinstein Company

– Open Road

– Sony Pictures Classics

– Roadside Attractions

– Relativity

– Sony Pictures

– Radius-TWC

– Magnolia Pictures

– Samuel Goldwyn Films

– Lorimar Motion Pictures

– Cohen Media Group

Gross of $100,000-$2 Million

– IFC Midnight

– China Lion Film Distribution

– MacGillivray Freedman Films

– Zeitgeist

– GKIDS

– Counterpoint Films & Self-Realization Fellowship

– Area 23a

– Eros Entertainment

Gross of $25,000-100,000

– International Film Circuit

– First Run Features

– Music Box Films

– Dada Films

– Aborama Films

– Strand

– Drafthouse Films

– Oscilliscope Pictures

– Rialto Pictures

Since this list comes from only one month of box office listings, other distributors may show up if these listings were drawn from other months, several months, or a year.

And what if you don’t have the luxury of choosing among many distributors, since you only have very few offers, even only one? Then, make the assessment based on whether you want to select this distributor at all or either wait for another distributor or self-distribute your film, at least for a awhile.

In sum, if you have one or more distributors to choose from, in making an assessment, factor in the distributor’s track record along with other considerations to decide which one or ones to go with for your film. To make the best choice, the art of picking the right distributor or distributors (including the right foreign sales agents or agents) can be an involved, time-consuming process – from finding interested distributors to finding the right one or ones to work with. But it’s important to make this assessment carefully; it’s like entering into a short-term marriage, and if it works, you want to renew it; if not, you move on and look for other possibilities. Just carefully assess your options, in light of what’s realistic for your film, so you start out with a good marriage for your film.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on films: HOW TO WRITE, PRODUCE, AND DIRECT A LOW-BUDGET SHORT FILM and FINDING FUNDS FOR YOUR FILM OR TV PROJECT. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 feature scripts, and has one feature she wrote and executive produced to be released in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gus | Jan 9, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

Once are ready to approach distributors, how do you know what to expect based on your type of film?

First, decide what is realistic for your film, aside from making the best presentation you can with your trailer, screener, synopsis, and press materials. In general, if you have a low-budget independent film with no names, you can expect many distributors not to be interested, or only interested in non-theatrical outlets, unless you have a very unique project with strong production values and have gotten a lot of interest through a PR campaign. This is where any showing at a top tier festival or a string of awards at other festivals can help you land a top distributor. There are a small number of films that have risen above the pack by standing out in some way, such as The Blair Witch Project or Paranormal Activity. But these are the one in a million breakthroughs.

As much as you may want a theatrical release because of the added attention and prestige it brings to distributing a film through other channels, it is often not the best approach for most low-budget films. That’s because of the high costs of such a release and the lack of financial return from most theatrical showings, unless there is a big box office success, since there is a low return for each ticket sold. The theater owner typically takes at least 50% and sometimes up to 75% when the film is first shown until it makes a certain amount. So you may not make back the expenses for the release. The main value of the theatrical release is that it’s like a promotional loss leader at a retail store to get customers into the store where they’ll buy more. As such, it helps to create more interest for viewers to buy or rent the video or look for it on Netflix or other outlets, including your website for DVD sales. But the release can be economically unfeasible. And some low-budget genre films, such as horror, suspense/thrillers, and action adventure films, don’t normally get a theatrical release – they go straight to DVD, streaming, downloads, foreign, or other types of sales.

Secondly, when you contact distributors about your film, whether in person, by phone, or email, don’t put information about the stars or budget up front, unless you have at least one name star and a budget of $1 million or more. One good approach is to initially tell distributors about the genre and logline to see if the subject is of interest. If so, briefly describe the highlights of the film, such as the major plot points and any press coverage, awards, or large following you have gotten. If you do have a big name attached, put that front and center, and if the budget is over a million, you might showcase that. Otherwise, it’s best not to state the budget until a potential distributor has expressed interest, and if it’s a very low budget, just say it’s under $200,000.

Typically, once the distributor has some initial interest after learning about the project and possibly seeing a trailer, one of the first things they will ask is “Are there any names?” and “What is the budget?” – the questions that most distributors asked me when I pitched them SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE. Besides asking for this information, distributors will want to see the screener to decide if they still want to distribute the film. Though they don’t ask for this, when you send the screener, it’s best to include it in a box with compelling art work and other information about the film in a press kit, which can often be online as an electronic press kit. When your screener and promotional materials are ready, either mail the kit or send the link, which is what we did for SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE. Having this professional looking box for your screener is very important. Don’t send your screener in a plain disk cover, which looks tacky and can be a big turnoff. As for what to include in your press kit, I’ll discuss that in a future article.

Do not reveal the actual budget if it’s a very low one, because that can turn off a distributor. Stories like El Mariachi, who has claimed having a $7000 budget for a film that became a multi-million dollar box office success story, are the exception to the rule. And even if you made your film for a very low amount, say $5000 to $25,000, there may be deferred or work for credits deals with the cast and crew that if paid up front would make your budget much more. There might even be specials on locations and equipment used in the film, so you got them for no money or a super low price, but they are worth much more. For example, if you factor in the real value of the work of the cast and crew, the house used as a shooting set, and the cameras and sound equipment used for filming, you might find your budget was actually around $250,000, whereas you paid only $25,000 up front. So in talking to prospective distributors, use that higher number. Later, after you have gotten your deal and gained success for your film, you can talk about the real budget, which can make a great story to get you more press for your film. But initially, a distributor is apt to feel a very low-budget film isn’t going to be very successful and not want to distribute your film.

In deciding on a realistic distribution approach for your film, consider whether you hope for a theatrical deal or not. While a traditional theatrical deal, such as a studio pickup, might not work given the type of film, lack of names, lack of a following, and lack of budget to cover P&A, you might consider a limited roll-out approach. That could lead to future theatrical distribution as well as helping you distribute in other channels, because of the prestige and press value of opening in a theater. This is what some independents do — a “platform” roll-out, where the film is first shown in one or a few theaters. If it does well and gathers press and distributor interest, it expands to additional theaters, or it could be picked up after the opening by a distributor or studio for additional theatrical distribution. Should you go this route, you often have to pay for the theater and local advertising and promotion, commonly about $5000-15,000 for a week’s run, with the cost depending on the theater, location, and any travel expenses for you and/or others from the film to be there for the screening and doing any advance marketing to build the audience. However, it’s best to only go this route if your film is unique in some way, and you have a budget to support a theatrical showing, so it stands out in a crowded marketplace. Otherwise it’s best to skip a theatrical release.

If you decide not to pursue theatrical screenings, let the distributor know you aren’t expecting this, unless the distributor can make a strong case of why to go theatrical. And even if you arrange for a showing in one or a handful of selected theaters, this still might not mean you are seeking a wider theatrical release. Another reason for having a small number of screenings in theaters is to get some press coverage you can use to support distribution in other channels. These showings could also be a way to build your following on the social media, such as LinkedIn, Facebook, or Twitter, to see your film. Also, you might invite prospective distributors to see your film in a private or public screening, in lieu of or before getting a screener, such as one client who invited several hundred distributors to two showings she arranged for in New York. Should you decide not to go theatrical, look for distributors who are strong in other types of distribution.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on films: HOW TO WRITE, PRODUCE, AND DIRECT A LOW-BUDGET SHORT FILM and FINDING FUNDS FOR YOUR FILM OR TV PROJECT. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 feature scripts, and has one feature she wrote and executive produced to be released in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gus | Jan 7, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

Now that you are set up for assessing interested distributors and foreign sales agents (which I’ll often call distributors now for convenience), how do you find them to get them interested and assess the best ones for you?

The main ways to find and connect with them include the following:

– Go to film markets, such as the American Film Market, and meet with exhibitors or obtain their names from a list of distributors and phone or email them after the market, since most of the exhibitors are the biggest distributors or sales agents. The other major film markets, according to an article “Top 14 Film Markets” by Minhae Shim in Independent’s Guide to Film Distribution include Hot Docs, held in Toronto, Canada; the Independent Film Week/Project Forum in New York City; INPUT (International Public Service Television Screening Conference); the National Media Market, in Charleston, South Carolina, and NATPE (National Association of Television Executives) held in Miami. The other major film markets are outside the US and Canada – CineMart in the Netherlands, the European Film Market in Berlin, the Hong King International Film and TV Market, the Marche du Films and MIPTV in Cannes, and TIFFCOM (Tokyo International Film Festival Content Market).

Most realistically, the one to go to is the American Film Market, held in Santa Monica in early November. I attended it several years ago, and have since obtained information on the exhibitors who are listed publically, and I am now a member of the AFM365, which provides a way to contact other attendees during and after the festival for the following year. If you go to this festival, you can get a pass for the whole festival for $795 or for the last 3 days for $295. Either pass will enable you to go to the showrooms, where you can meet distributors, though most filmmakers on a low budget buy the 3 day pass and hang out in the lobby on other days to meet people who are there. You have the best opportunity to meet exhibitors on the last three days, since on the first four days, they are focused on speaking to buyers and making deals to sell their films. If you have a packaged screener, it is best to set up meetings with distributors in advance, although you can also go to their showrooms when they aren’t busy. If they are interested, you can leave your screener and any press materials with them, or get their business cards or other contact information and send the screener later. If you don’t yet have a screener, simply introduce yourself and get their business card or flyers with contact information for follow-up later. And even if you only get their contact information because they are too busy to see them, that’s fine, since you can contact them later by phone or email.

However, don’t expect to make any deals at the AFM or other film markets. Unless you have big names attached, the distributor will want to see your screener first.

– Go to conferences, workshops, and panels which feature distributors and sales agents. This can be a way to personally meet a few of the speakers and panelists who are distributors or can refer you to them. You probably will only be able to say hello and maybe ask a question or two. But get the contact information for later follow-up once you have a screener ready, and in your follow-up, mention that you have met the person at the event you attended. In some cases, conferences and workshops will provide attendees with a directory of distributors, such as a film funding conference I attended several years ago in Los Angeles which was put on by the Independent Film Forum. Whether you meet a distributor personally or get their name from a directory at the event, it’s generally best to send a query letter or call first rather than sending in the screener and any press materials unless requested to do so, since different distributors have different procedures for requesting material. Tell them what you have to send them, and they can tell you what to do next.

– Research the names of distributors in different directories and industry listings. Doing this research can be a time-consuming process, but much of this information is available for free or at a low cost. Here are just some of the lists of distributors that are available:

– Independent Filmmakers Showcase’s “Independent Film Distributors List”

(http://www.ifsfilm.com/Resources/Distributors.php)

– Video University’s “Video and Film Distributors”

(http://www.videouniversity.com/directories/video-and-film-distributors)

– Indiewire’s “Guide to Distributors at Sundance 2014”

(http://www.indiewire.com/article/distributors-guide-to-sundance-2014)

– The Numbers “Market Share for Each Distributor 1995-2014”

(http://www.the-numbers.com/market/distributors)

– Film Journal’s “Distribution Guide” to Domestic and International Companies

(http://directories.vnuemedia.com/fjiguides/distguide)

– Insider’s Guide to Film Distribution, edited by Minhae Shim, Erin Trahan, and

Michele Meek, Independent Media Productions, Cambridge, MA.

– The Producer’s Insider Guide to Selling Films – Film Distributors Directory by

Amemimo Publishing.

If you put “film distribution directories” in Google search, you’ll find even more. You can use these directories to find distributors for your type of film. Then, write to them about your film and ask if they want to see a screener. If they are interested, send it and go from there.

– Use a query service to send a query for you to distributors. Instead of doing all of the research to create a list of distributors to contact yourself, you might use a query service, such as Publishers, Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), since it has already done this research for you and can send out a query to 1000 plus distributors, including AFM exhibitors for the past two years. The advantage of using this service is the company has gone through all of these directories and created an email list, so you don’t have to spend the 20 or more hours to create your own list. Plus the query goes out under your email using their special software, so the responses go directly to you, and they help you write a good query letter.

That’s what we did in distributing SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE, and 20 distributors expressed interest after our initial query with a link to the trailer. Then, we will send another query once the screener is ready to follow-up with those who have already expressed interest as well as to others, since they may be interested now. Some other filmmakers used this service several times to invite distributors to a series of showings they set up for private screenings in Manhattan.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on films: HOW TO WRITE, PRODUCE, AND DIRECT A LOW-BUDGET SHORT FILM and FINDING FUNDS FOR YOUR FILM OR TV PROJECT. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 feature scripts, and has one feature she wrote and executive produced to be released in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gus | Jan 7, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

Once you know the different players in the distribution space and the different possible channels of distribution, the next step is creating your distribution plan. To this end, consider the audience for your film, the size of this audience, and how to best reach them. Also, consider the realistic potential of your film and its likely appeal to a distributor or festival audience, so you don’t let your dreams of great success overwhelm a realistic assessment of what your film is likely to do in the marketplace.

Additionally, consider the cost of different types of distribution or entering certain festivals to seek distribution, such as the P&A (promotion and advertising) costs for a theatrical release or entry fees for festivals, along with travel expenses if you win and want to attend. Such expenses are in addition to the expenses for deliverables that every distributor and sales agent will want if they take your film, such as creating different digital and DVD formats for distribution, along with preparing DVD covers and cover art, posters, press releases, and more.

Some people may think, “Oh, I’m just going to crowdfund for the additional money I need,” and that approach can be fine for many films, most notably those that already have a fan base of friends, family, and supporters, so you can raise at least 25-30% of the needed funds from this inner circle. But if your circle is largely composed of other filmmakers, who are seeking to raise money for their own films, hoping for funds from them may be unrealistic, as may be gaining the funds from strangers contributing to your campaign. Moreover, the crowdfunding space has become very crowded these days, with so many people thinking they can gain the money they need this way. But the stats from crowdfunding sites tell a different story – only about 40% of Kickstarter projects get funded, and only about 13% of Indiegogo projects reach their goal, although they may get some funds along the way. Further, you have to factor in the cost of commissions and payment fees on whatever money you raise (about 8-15%), as well as the cost of the perks you are providing to funders. So often it may not be realistic to expect to fund your film through crowdfunding, though some projects do succeed or gain a major proportion of their film’s budget this way.

Secondly, be realistic about what film festivals you can get into, and whether it’s worth waiting to first build up your platform through festival showings and awards in order to seek a better distribution deal than you might get before entering the festivals. Often at my Film Exchange Programs and other film events, I have heard filmmakers who are completing or have just completed their first film say with perfect confidence that “We thought we’d start by showing the film at Sundance” or fill in the name of any of the top film festivals. However, the reality is that you have low odds of getting into these top festivals. For example, Sundance averages 5000 plus submissions for about 200 slots, and in most festivals, the festival staff and directors are apt to give priority consideration to filmmakers they know or to films with big names that bring prestige to the festival. So that leaves about 10-15% of the slots available for new filmmakers, and if you have a low-budget film with no names, you are unlikely to get in.

Even if you do get into one of the big festivals, where distributors go, such as Sundance, Toronto, and Cannes, to get a distributor to see your film, you need to build up excitement about your film in advance. And that usually requires hiring a publicist to promote your film, which costs several thousand dollars. Plus even getting into a top festival doesn’t guarantee you will get a distributor, since the distributors only pick up a handful of films at these festivals. It can help you get a distributor if you can build up enough excitement to get distributors to go to the first showing at a festival, since that’s where more of the deals get done, while a smaller number of distributors commonly show up at later showings. Yet, even if the distributors see your film, there are no guarantees that a festival launch will result in a distribution deal. Thus, with a low budget no name film it can be especially unrealistic to consider getting into the big festivals, and even if you do, you might still not get a distributor. Moreover, with these long odds, you have to wait before releasing your film anywhere else, so you can premiere it at the festival.

What might be more realistic is entering the second and third tier festivals, where you don’t have to premiere, either before or after you get a distributor or obtain multiple distributors for different channels and territories. Your odds of getting into these smaller festivals are greater, especially if the film’s director or top cast or crew personally know the festival director or staff members. Then, you can use that acceptance and any awards to help build your film and company’s platform, and you can incorporate those awards into your press releases or query letters to the media to increase your chances of getting a distributor or press coverage – or getting into more festivals.

As to whether to enter and publicize any festivals where you are accepted or win awards before or after you get a distributor, either is fine. If you don’t already have a distributor, inform the distributors considering your film about any festival acceptances and awards, which might help you get a distributor or sales agent. Attaining a number of festival showings and awards might also give you more leverage to get a better distributor with more clout or obtain an even better deal. Alternatively, if you already have a distributor or sales agent, any festival acceptances and awards can help them market and publicize your film.

One way to decide whether to line up distribution before or after the festival or start with some distributors and get more afterwards for different channels or territories is to approach distributors and agents before the festivals. Then, you can decide what to do, based on the number of offers you get before the festival and the quality of these distributors and agents. If you have an offer from one or more good distributors and agents, great! You can make some decisions in advance and use your festival participation and any awards to support your distributors and agents. Or you can delay your decision until after the festival if you aren’t sure and hope to find other distributors or get a better deal through your festival participation.

As an example, that’s what we have been doing with SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE. Once the trailer was available for viewing on YouTube, I did a mailing to invite about 1000 distributors, sales agents, and AFM exhibitors using the query service, Publishers Agents and Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com) to tell them about the film and invite them to view the trailer and let me know if they were still interested in distributing the film. About 20 distributors and agents expressed interest, though they wanted to see the screener first – which is typical, unless you have big names in your film. Then, the director and I researched the background of each prospective distributor and agent on IMDB and other sources to see how many films they had previously distributed and how these films had done. Probably, if we have a reasonably good deal from the best of these distributors, we will at least sign some distributors or agents for some territories and channels. But if we aren’t satisfied with these distributors’ or their offers, we will go to some festivals and decide among the interested distributors and sales agents after the festival.

Likewise, you can work on getting distribution before or after these festivals. Just be realistic about what kind of deal and distributor or sales agent you might expect for your film, so your dreams don’t outpace a likely distribution scenario.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on films: HOW TO WRITE, PRODUCE, AND DIRECT A LOW-BUDGET SHORT FILM and FINDING FUNDS FOR YOUR FILM OR TV PROJECT. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 feature scripts, and has one feature she wrote and executive produced to be released in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gus | Dec 25, 2014 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

Today, there are more channels than ever for distributing your film. Since many distributors specialize in certain channels, you may want to consider dividing up the distribution among different distributors, as long as their territories don’t overlap if you have exclusive deals. In other cases, distributors will ask for all rights in all channels within a certain market, such as domestic (US and Canada), foreign (all countries outside of the U.S. and Canada, or certain countries or regions), or worldwide.

Thus, it can become very confusing to sort through who wants what channels in what territories, besides looking at the range of deals offered in terms of percentage split, types of deliverables required, such as DVDs and digital files, and the amount of money needed from you, if any, for P&A (promotion and advertising), or whether you will get any upfront money on signing the deal (which is generally no if you don’t have any recognizable names in your film).

One way to help sort through the varying offers is to create a matrix where you list the required and desired channels for each distributor, along with the territories required and desired. Your matrix might look something like this:

Across the top: All Channels, Theatrical, Home Video, DVD, and so on.

On the side: Worldwide, Domestic, All Foreign, Latin America, Eastern Europe, Asia, etc.

Then, in each box, list the name of the distributor who has expressed interest in that channel and territory, and note if the distributor requires (R) or desires (D) that channel and territory for the deal. You can also indicate of the distributor wants an exclusive (E) or non-exclusive (N).

As you get expressions of interest from different distributors, you can enter their name in the matrix. Also, review their track record and offers. As you do, you can rate the distributors to create a priority list (such as ranking them from #1 to #5, with the top rank being #1, or rating them from 1 to 10, where the higher the number, the more you like them). Use whichever system you prefer – a ranking or rating system. Then, put that number in the box for each distributor listed, along with whether this channel is required or desired and whether the distributor wants an exclusive or non-exclusive. The result should look something like this for one box: Distributor Smith. #1, R, E; Distributor Jones, #3, D, N.

In making these deals, you will commonly retain the direct sales rights, which means you can sell DVDs from your websites and at screenings, and often you may have the right to sell downloads and streams from your site, unless the distributor wants to restrict such sales. Ideally, it’s best to retain direct sales rights, because you will have a greater profit margin, a faster payment, and don’t have to split your income from these sales with a middleman; you only have to pay the manufacturing and fulfilment costs. Also, by retaining direct sales rights, you can sell other products if you have merchandise associated with your film, such as T-shirts, hats, posters, mugs, soundtrack albums, or a book based on your film. Plus you can sell related products from others that might appeal to your audience, such as books and DVDs, which you buy at wholesale and sell retail. But if you aren’t set up to handle sales and fulfillment yourself, it may not make sense to keep these rights if the distributor wants to do this and give you a share of the proceeds.

According to Peter Broderick, author of “The Twelve Principles of Hybrid Distribution,” in a recently published book: Independent’s Guide to Film Distribution, the major channels of domestic and international distribution can be listed as follows:

Domestic: Festivals, Theatrical, Semi-Theatrical and Nontheatrical, Cable VOD, SVOD, Television, Direct DVD, Retail DVD, Direct Digital, Retail Digital, Educational, and Home Video.

International: Festivals, Television, Direct DVD, Retail DVD, Direct Digital, and Retail Digital, and occasionally Theatrical and Educational Distribution.

Splitting up the rights among different distributors handling different markets can be complicated and time consuming when you get a number of offers to consider. But an advantage to splitting the rights is that you can get better distribution when different distributors are especially strong in a particular channel or channels, so you can have another distributor handle those channels where another distributor is weak. Then, too, as Broderick notes, this approach avoids cross-collateralization, whereby the expenses from one area of distribution are applied against revenues from other areas of distribution.

Also, in splitting up rights, decide if there are certain areas where you want to retain the distribution rights, because you feel you can successfully handle that type of distribution on your own, such as contacting the educational market or selling direct DVDs or digital copies from your own website or from a dedicated site for the film.

In assessing the distributors for different channels, find out which channels they handle well by asking about their track record. That can help you decide which distributor would be best in handling a certain channel. Also, as possible limit not only granting an exclusive, but the term of distribution and the level of performance expected, so you can assess how well the distributor is doing with your film during a certain time period (such as 6 months or a year). Then, if the distributor is doing well, great; you can mutually renew the agreement. If not, you are not stuck in an agreement, and you can either end the contract at the end of the term or for non-performance. These agreements can get complicated, so do have an attorney or someone familiar with distribution agreements review them and make suggestions about what to add or change, as necessary.

Finally, be careful that the rights you give to different distributors for different channels don’t conflict, but are complementary, and that the rights given to a distributor for different channels and territories don’t restrict you from making deals for other channels or territories. Ideally, make all the deals at the same time and try to keep them to the same term, so you can better keep track of when deals expire or are up for renewals.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on writing and publishing books: FIND PUBLISHERS AND AGENTS AND GET PUBLISHED and SELL YOUR BOOK, SCRIPT, OR COLUMN. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 scripts for features, and has one feature film she wrote and executive produced scheduled for release in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which have meetings to discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gus | Dec 25, 2014 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Books, Marketing Tips - Films

One issue that frequently comes up in workshops or online forums is whether you need a copyright for your film or book. Occasionally people ask if they can use what is sometimes called the “poor man’s copyright,” where you send yourself your material in a sealed envelope, so you can later prove that you wrote it when you did.

First, the “poor man’s copyright” is perfectly useless. It is a myth that makes the rounds from time to time, usually because someone has just heard about it from someone else and wants to find out if it is true. Well, it isn’t. At best it might establish a date of mailing. But there are so many loopholes in that mailing to make a proof of anything problematic. A big problem is that one can easily steam open an envelope or mail an unsealed or empty envelope to oneself, and then put the document in the envelope and seal it up after the unsealed or empty envelope comes back in the mail.

Another misconception is that you need to formally register a copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office in order to have a copyright. But you actually have a copyright from the date of creation once you write your book, script, article, proposal, or anything else. You are similarly covered by a copyright when you draw something, compose music, record a song, or otherwise create anything and record it in written, visual, or aural form, though you can’t copyright an idea or title. A title might be covered by trademark, if you are using it or intend to use it; but that’s a more complex subject, since you can choose from multiple categories in which to register a trademark, and you can run into complications when you use a trademark in one geographic area and another person creates the same or similar mark in a different geographic area, depending on what categories you each are claiming. But for all practical purposes, if you write a book, book proposal, script or other written materials with hopes to get it published or produced, you are dealing with copyright law and the Copyright Office in Washington, D.C.

So essentially the question you are really asking is: “Should you ‘register’ a copyright?” with the U.S. copyright office. If you are writing a script, there is also a possibility of registering it with the WGA, either in Los Angeles or New York, though most register it in Los Angeles, and some producers and agents/managers may ask you to do this. However, that’s not the same as registering a copyright with the government; a WGA registration is more like just putting it on a list that establishes your date of conception, and then you have to renew the WGA registration every 5 years if you register it in L.A., every 10 years if you register in New York.

By contrast, registering a work with the Copyright Office gives you a registered copyright as of the day of registration. The most efficient and economical way to do this is to register online, which is currently only $35 for an individual copyright, meaning just one item is being copyrighted by one author. If there are more authors or this is a combined registration of different properties, it is $55 to register online. It costs more to go the old fashioned postal mail route — $85 — and it will take 2 months or more to get your registration. Ideally, go through the online system, where you pay and are walked through a step by step process to answer each question about the name of the author, date of registration, and other data. Then, your answers are entered into the copyright form which goes to you.

The costs can mount up if you have multiple items you want to register, so you might consider whether a copyright is really necessary. Take into consideration the fact that a copyright gives you the right to pursue your rights online or in court, but you have to take any actions to enforce your copyright, which can be time consuming and expensive. For example, the most cost effective way of using a registered copyright is to prevent someone else using your material online, such as by sending this information to the offending website owner or to a web hosting company which is hosting a website with your copyrighted material. You just send a take-down notice with evidence of your copyright, and normally the hosting company will take it down if the website owner doesn’t.

However, it is very expensive to take any legal action in court to enforce a copyright, so a registration won’t be of much use if you are seeking compensation from someone who has improperly posted your material online and they don’t have any money. But if you wait, maybe they will or they may arrange for someone else to use your material – at which time, you can inform them that you own the copyright and you aren’t giving your permission without a just compensation, whereupon you can negotiate the terms with them if they willing to do anything. Otherwise, you have the basis for taking them to court and claiming statutory damages, which may lead them to drop your material or seek an agreement from you.

In general, given the expense and limitations of a copyright, it is not necessary to register the copyright for a proposal or manuscript. The situation is different if you self-publish a book or if a traditional publisher publishes it and normally assigns the copyright to you. In this case, the publisher will generally take care of filing for the copyright in your name. If not, it is a good idea to file for copyright yourself, especially if you feel the book has a good commercial value for a general audience, since there is more risk of someone using your material or even filing a registration on a copy of your work.

Otherwise, if your work is unpublished, it may not be worth the time and expense, since publishers and agents are unlikely to use your material without you, since a key interest is in having you as the author be front and center to promote it. And normally there isn’t the kind of money in a published book as there is in a produced film or a recorded song. So with a book, unless it just makes you uncomfortable to not register a copyright, I feel it isn’t necessary – especially if you have written many books, because of the high cost involved. And even if you self-publish a book, it may not be necessary to register a copyright, especially if you have published multiple books, making it expensive, since most self-published books average about 150 copies in sales, and if someone pirates your book, it probably doesn’t matter whether your book’s copyright is registered or not, since it is unlikely you can do much more than send a take-down notice to the multiple sites offering free copies of your book and hope they take it down. But if they don’t, it’s not normally cost-effective to try to pursue matters any further.

Likewise, if you write articles it is not necessary to copyright each one, especially when you are making the articles available for free. Just use them for promotional value, though if you combine the articles together into a book and self-publish it, you might get the copyright then.

By contrast, if you complete a script, treatment, or TV series or show proposal, it is a good idea to register a copyright, whether or not you have sought a WGA listing. Many producers for their own protection will want you to have a registered copyright, and often any NDA document they ask you to sign will have some language about your having only the protection that resides in what you have copyrighted and not to any similar ideas they might have developed in house or which they obtained from another writer or other party.

Another reason for registering a copyright in the film world is because it is so competitive, and sometimes, if a script reader sees the potential in your idea, it could be shared with others, though it might undergo some further changes in the script. Then you could be out of the loop, although a registered copyright will make it more likely for you to be involved in the project going forward. Or it could lead to a payoff to get the previously stated rights under the agreement signed over from you.

In sum, in the case of books and articles, it is generally not necessary to get a copyright unless you have high hopes for a large commercial sale or are willing to pursue take-down notices or a court case against someone who copies and sells your book and has the money to collect if you win. But if you write a script, TV series or show proposal, or treatment, do get your material registered, since you will often need it to even get your script considered by producers, agents, managers, or others in the film industry.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on writing and publishing books: FIND PUBLISHERS AND AGENTS AND GET PUBLISHED and SELL YOUR BOOK, SCRIPT, OR COLUMN. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 scripts for features, and has one feature film SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE, which she wrote and executive produced, scheduled for release in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which have meetings to discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gus | Dec 16, 2014 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

I’ve recently started thinking about how to best distribute a film, since I have been looking for distribution for my first feature film: SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE. This is the first of a series of posts which describes what I have learned is the best strategy and what to expect in the offers you get, so you can get the best deal possible, based on what’s realistic for your film. I’ll discuss both DYI (do your own) distribution if you can’t find a distributor, as well as different tracks to consider in distributing your film through different channels. Eventually, these posts will be collected together to create a book on DISTRIBUTING YOUR FILM.

First, know the major players in the film distribution space. The ones to contact depend on what your goals are for your film, such as whether you feel you have a film that merits theatrical distribution, or you want to focus on distribution in other markets. These major players include studio distributors, independent distributors, producer’s reps, and sales reps.

The studio distributors are largely out of the picture for independent films, unless you have a big breakthrough at one of the top film festivals where the big distributors go (Sundance, Toronto, and Cannes, and secondarily Tribeca, and maybe Berlin and Venice, plus some distributors go to South by Southwest. Such a film breakthrough requires not only being shown, but also creating an exciting talk or buzz about your film with an advance media build-up. Moreover, if you are aiming for the big festivals, you have to premier there, which means waiting to find out if you are accepted before you can submit to other festivals. However, the likelihood of acceptance is very small unless you have personal connections, since not only do the big festivals select a small number of films from thousands of submissions, but generally the vast majority – perhaps 85-90% — of those accepted come from personal connections with the festival director or staff, leaving only about 10-15% to be accepted on their own merits. Then if you are accepted, you still have to create that exciting buzz for your film to actually get a deal besides simply showing at a big festival. In short, for most indie filmmakers, a studio distribution deal is unlikely, though possible, should you later develop a great deal of excitement, so the studio distributors want to take a look at your project.

Then, there are the independent distributors, who come in all flavors. There are some who handle theatrical distribution, ranging from those who handle one or two films – generally their own films — to those handling a half-dozen or more. Many of these distributors will also handle distribution in other channels, such as to home video, cable, and foreign sales. Then there are many distributors who eschew theatrical for distribution in other channels.

Often if you want to seek a theatrical release, you will need a budget for P&A, which means promotion and advertising, along with the costs of any files, DVDs, posters, and local advertising, which you need for each theater, which can add up to $5000-10,000 or more per city, though normally you don’t pay the distributor. Rather, you typically make a split of the income arrangement, which is commonly 35-50%, though more often a 50-50 split, and in some cases, a distributor who wants your film enough will advance the P&A.

Some distributors may additionally ask you to have E&O insurance, which refers to “Errors” and “Omissions.” Even though your film is already produced, some distributors may still ask for this, just in case, such as one distributor interested in SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE explained to me. “Maybe a scene in the film might show a store or company in the background, and they object to the way they are portrayed. So this could trigger a request for a recut of the film or a lawsuit, but your E&O insurance would cover this.” On the other hand, most distributors I spoke to didn’t require this.

While some distributors will ask for worldwide rights, others just want domestic (which includes Canada as well as the U.S.), and some specialize in foreign. So everything is negotiable including what markets a distributor will handle, the percentage split, and how much P&A budget you will need if any.

Another major player is the producer’s rep. This is essentially a middleman who contacts distributors and foreign sales agents on your behalf and negotiates a deal for you. Commonly these reps handle a slate of films for different producers, generally about 5 to 20 other films, depending on the size of the rep’s company. Commonly the rep get 5-10% of the deal, occasionally 15%, depending on what they do. However, the reps should not take any upfront money from you, though some may ask for this. But they should only get an upfront payment if they are doing extra work, such as writing releases and creating posters for you.